Six Sigma Tools and Inventory Management

Growing up in the 1990s, you might have heard the term “Six Sigma” at the dinner table or in the news. It is not the name of an elite special forces team. Instead, it refers to a quality management improvement process used by large scale manufacturers. In reality, Six Sigma aims to keep product variation and thus defects to a minimum.

At first glance, there may not be much synergy between Six Sigma and inventory management. The first one is a highly disciplined approach to improving manufacturing processes, products and design. The second is about controlling and managing the stock of raw materials, semi-finished goods and final products. However, we shall see how Six Sigma learnings apply to stock control as well.

Here, we’ll cover what this quality-improvement practice means and what it involves. Next, we’ll explore whether it is still relevant today and what it means for inventory management. Finally, we’ll finish by exploring Six Sigma methodologies and tools used in modern Lean Six Sigma and Lean Inventory Management.

Quick Links

What is Six Sigma?

Six Sigma describes a set of techniques and tools for process improvement. Motorola engineer Bill Smith and psychologist Dr Mikel J Harry co-founded this approach in 1980. The term comes from statistical modeling of manufacturing processes. A sigma rating is a percentage of defect-free products. Thus, Motorola set a goal of six sigma for its production target.

Most famously, Jack Welch made Six Sigma central to his business strategy at General Electric in 1995. By the late 1990s, about two-thirds of Fortune 500 companies had Six Sigma initiatives. Their aim was to reduce costs and improve quality. In 2005 Motorola credited over US$17 billion in savings to Six Sigma alone.

Six Sigma was different from other quality-improvement efforts at that time. Firstly, it established clear, measurable and quantifiable targets for projects. Secondly, it emphasized top-down leadership and support for quality targets. Thirdly, you made decisions based on data and statistics rather than assumptions and guesswork.

A. Six Sigma Methodologies

Six Sigma uses two project methodologies known by their acronyms DMAIC and DMADV. Both of them use 5 distinct and sequential steps. Collectively, their aim was to improve business processes or produce a better product or service. Later, you will see later that these two methodologies underpin future lean management principles.

1. DMAIC

DMAIC is used to improve manufacturing processes:

- Define. Define the system, the voice of the customer and their requirements, and the project goals.

- Measure. Measure key aspects of the current process and collect all relevant data.

- Analyze. Analyze the data to investigate and verify cause-and-effect relationships.

- Improve. Improve or optimize the current process based upon data analysis.

- Control. Implement control systems to observe any deviations before they result in defects.

2. DMADV

DMADV is typically used to create a better process, product, or service. It is also known as DFSS or Design For Six Sigma.

- Define. Define design goals that are compatible with customer demands and the business strategy.

- Measure. Measure and identify product capabilities, production process capability, and risks.

- Analyze. Analyze to develop and design alternatives.

- Design. Design an improved alternative

- Verify. Verify the design and implement the production process.

B. Implementing Six Sigma

Six Sigma uses a set of statistical quality management methods. It also creates a special organization chart of people in the business who are experts in these methods. Each project follows a defined sequence of steps and has specific targets. For example, to reduce process cycle time, reduce pollution, lower costs, or increase customer satisfaction.

Six Sigma also implements a quality management hierarchy with titles inspired by the martial arts. Champions, for example, take responsibility for Six Sigma initiatives across the organization. Master Black Belts are in-house Six Sigma coaches. Black Belts then apply the methodology to projects. Green Belts describes employees involved with Six Sigma projects.

Some organizations have adopted and taken the ranks even further. Yellow Belts are employees with basic training in Six Sigma tools and generally participate in projects. White Belts are those trained in the concepts but do not participate in projects. Orange Belts are reserved for special cases.

C. Is Six Sigma Still Relevant Today?

As you can guess from its success with large Fortune 500 companies, Six Sigma is best for very large organizations that manufacture products. The methodology needs to be modified for firms with less than 500 employees. However, it does contain tools, processes, and techniques that are still useful for small to medium-sized businesses.

Critics of Six Sigma have noted that it is not a fix-all solution for all quality management issues. And, that much of it is outsourced to expensive consultants. However, it should be seen as a methodology that needs to be put into context. Hence, a holistic approach is needed to implement any Six Sigma initiatives rather than a band-aid approach.

Going ahead, the biggest challenge to Six Sigma is structural changes in the economy itself. Much of the 1980s and 1990s were dominated by brick-and-mortar manufacturing giants. The decades that followed saw the birth of New Economy with the growth of services and software firms. These do not involve the manufacture of physical products. Hence, Six Sigma is far less relevant to them.

D. Six Sigma Looking Ahead

In recent years there’s been a trend towards simplification and efficiency. Think agile software development and lean management. They share similar concepts with Six Sigma but have different end goals. Lean management uses standardized tools and methodologies to promote efficiency and eliminate waste. Six Sigma, on the other hand, focuses on production consistency.

You might be forgiven to think that Six Sigma is no longer relevant today. The economy is seeing a structural shift from old-world manufacturing to new economy retail, services and software. However, you will shortly see that Six Sigma principles live on in newer methodologies. Businesses and academics are quick to adapt past schools of thought to fix today’s business problems.

Thus, an offshoot of this is the combination of lean manufacturing with Six Sigma. This methodology is called Lean Six Sigma. It sees both lean manufacturing and Six Sigma as complementary schools of thought. The first one addresses process flow and waste issues. The second one focuses on variation and defects in output.

Lean Six Sigma and Supply Chain Management

Inventory management plays two critical roles in Lean Six Sigma. Firstly, the management of raw materials and semi-finished goods in the lean manufacturing process. Secondly, inventory control of finished goods held in a warehouse by manufacturers. In both cases, you should keep a sufficient stock level to minimize inventory carrying costs.

As a component of lean manufacturing, stock levels of raw materials and semi-finished products need to be controlled and managed. Similar to Japanese kaizen and Just-in-Time principles, just the right amount of stock should be held to keep production schedules going. This will reduce waste and optimize the production workflow.

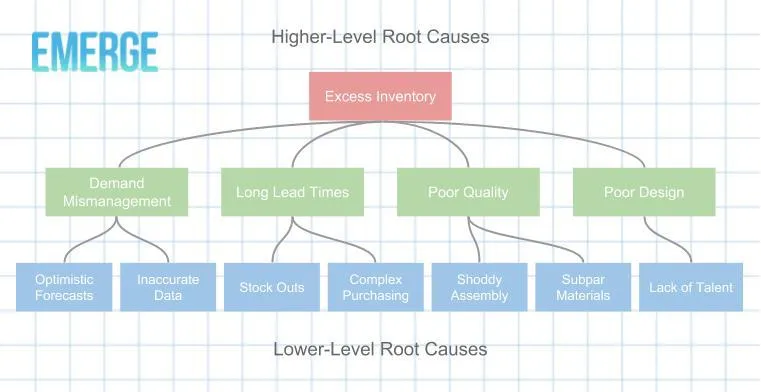

For finished goods, excess and obsolete inventory are major business issues. These often involve deadstock and seasonality. A typical solution addresses the excess inventory. You might sell them below cost or donate them, for example. But this does not address their root cause. Accordingly, Lean Six Sigma is used to identify and eliminate these root causes.

A. Lean Six Sigma in Action

Root causes in inventory management can be described as higher and lower-level root causes. Often, excess stock, dead stock and obsolete inventory is caused by higher-level root causes. These include purchasing lead times, forecasting, quality and design issues. Consequently, these can then be broken down further into lower-level root causes.

Long lead times, for example, may be explained by stock outs and purchasing workflows. Stock outs may be caused by the length of time it takes a supplier to ship out an order. Or an inappropriate reorder point that causes delays in replenishing stock. A Lean Six Sigma team would investigate the actual reasons for stock outs as well as other causes such as complex purchasing flows.

Another higher-level root cause is inaccurate demand forecasts. A Lean Six Sigma project team would likely look into the root causes of mismatched forecasts. These may include inaccurate demand data and wrong or poor forecasting methodology. Along these lines, there may be other business issues such as overly optimistic forecasts by the sales team.

B. Lean Inventory Management For The Future

Just as Six Sigma evolved into Lean Six Sigma for today’s decade, it stands to reason that lean management principles equally apply to inventory management. This results in Lean Inventory Management principles for businesses outside of manufacturing. This is especially so for wholesalers, distributors and retailers who deal in physical goods. Thus, you need not be a manufacturer to reap the benefits of Six Sigma.

Lean management, or Lean for short, is an approach to running an organization that supports the concept of continuous improvement. Accordingly, it is an ongoing effort to improve products, services, and processes. It has its roots in Japanese kaizen techniques. Thus so, Lean emphasizes incremental improvement to efficiency and quality over time.

Using lean principles in inventory management can result in quantifiable improvements for small and medium-sized businesses. Lean supply chain methodologies reduce costs, improve workflows, and increase profits. And, unlike Six Sigma, these benefits can be enjoyed by organizations of all sizes and not just large-scale manufacturers.

C. Principles of Lean Inventory Management

Like Six Sigma, there are five guiding principles in Lean Inventory Management. You can recognise some from past quality management and manufacturing principles of the past decades. Thus so, methodologies can adapt and evolve to suit pressing issues that businesses face today.

- Value. Identify the value that a company will get from Lean Inventory Management.

- Flow. Optimize the flow of inventory through the business by removing obstacles in the way. This comes from the Japanese 5S Lean principle (Sort, Straighten, Sweep, Standardize, Sustain).

- Pull. Move inventory only when requested by the customer. This is adapted from the Kanban Lean principle.

- Responsiveness. Be flexible and adapt to change. This is influenced by the Kaizen Lean principle.

- Perfection. Continuously refine your inventory management processes to improve quality, cycle time, efficiency and cost. This is derived from the DMAIC Six Sigma methodology.

D. Lean Inventory Management in the Organization

Applying Lean Inventory Management principles to a business will see a change in at least six areas of the organization:

- Demand management. You should only move inventory upon an order by a customer.

- Cost and waste reduction. But not to the extent of negatively affecting the customer.

- Process standardization. Standardizing, for example, on transportation and business processes.

- Industry standardization. Standardizing on product parts and components.

- Cultural change. Everyone along the supply chain must work as a team. Similarly, this echoes principles from Just-in-Time manufacturing.

- Cross-organization collaboration. Teams that cut across the organization can help to understand value better. Thus, it provides a holistic view similar to that of customer.

Conclusion

In conclusion, Six Sigma methodologies, approaches and tools still have a place in industry today. Its principles and tools have evolved over time. They have lent themselves to Lean Six Sigma and Lean Inventory Management methodologies. In kind, these newer initiatives include inventory management principles to reduce waste, lower costs, increase efficiency, and raise profits